| China: Birth and Belonging |

|

|

|

| Culture | |

| Sunday, 07 March 2010 | |

|

We, as Dimsum readers, all share an identity - a certain "Chineseness" - irrefutable for some, but much more elusive for others. However, the meaning of this identity is becoming increasingly problematical in a post-modern era when globalization is blurring national boundaries and rapid information transfer is highlighting regional differences within countries.

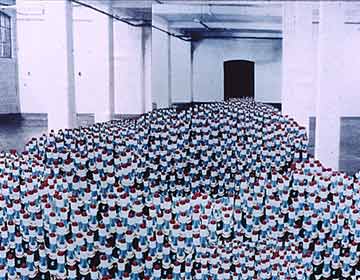

Art, Migration and the Complexity of Belonging  Li Yuen Chia (1929 - 1994) is popularly credited with establishing modern abstract art in Chinese circles. He moved to Brampton in the English Scottish Boarder in 1968 and purchased a derelict farmhouse which he turned into the LYC Museum and Art Gallery through his own effort and scant resources. Within 2 years, Li was awarded funding from the Arts Council which allowed the museum to continue for 10 year more than Li's original plan. Simultaneously, Li's art and warm personality has gained him respect from the local community. When asked who he is by a doctor at Li's deathbed, a local replied, "I am his next of ken". However, a lack of legal knowledge meant that Li was eventually hindered from selling the property and returning to China. His freedom became his prison. However, a thought-provoking point was raised by a member of audience who commented, "Li did suffer from the typical problem of Chinese migrants, but if we take away all his Chineseness, his difficulty would be no different from that of any other working class person." Li personally believed that ethnic identity meant little to him, for that his constant migration has given him a much more encompassing identity. "My heart belongs to nature, and nature belongs to my heart" he said. Finally, there is the example of the contemporary artist Anthony Key, who was born in 1949 in South Africa at a time when the five thousand Chinese did not even constitute an ethnic category. Growing up during the Black and White partition years meant that Key often had to make himself "invisible", an idea which he questioned in his art. His work Free Delivery (1999) placed little Chinese flags on the UK map indicating where Chinese takeaway food has been delivered, making visible what is otherwise invisible and unnoticed. It subtly revealed the postcolonial fantasy of Chineseness invading Britain and reflected the way second generation migrants empowered themselves through humour. Possessing a strongly hybridized Chinese identity, Key questioned if Chinese people are essentially the same in his 1997 work Yellow Peril, which used hundreds of soy source bottles to represent the way Chinese are flooding into the British boarder, illustrating Britain's absurd fear of Chinese immigrants invading and parodied the mentality that all Chinese look the same.  The One-Child Policy Unborn Life and Stem Cell Research in China Finally, there are certain historical policies and situations that are continuing to influence China's modern day identity. In 1977, China introduced the One Child Policy to control population growth, which led to many social issues, amongst which was the problem of abortion. Therese Hesketh, UCL Professor of Global Health, shared her insight on the policy's impact on the present day society, while Magaret Sleeboom-Faulkner, an expert of biotechnology and society in Asia, took a closer look at women's attitudes towards abortion and its significance within the context of global stem cell research. Chairman Mao once encouraged high birth rates, believing that population increase is an important contribution to a nation's rise to power. In the 50s, population increase became as high as 70% and by the late 70s, 2/3 of the Chinese population were under 30. However, social and economic problems of this rapid population increase led to the introduction of the One Child Policy in 1979, restricting urban families to have only 1 child and rural families 2. Such strict policy was successfully implemented because, firstly, rewards and benefits were significant. Offenders were strongly punished through the loss of jobs, fines and forced abortion if found pregnant, whereas policy abiding families were abundantly rewarded through low interest loans and health insurance. Secondly, the policy was introduced at a time when the government had control over almost all aspects of people's lives, meaning that people were unaware of the meaning of "freedom". Thirdly, propaganda was great in the 80s, with posters everywhere advertising for the economic benefits of having one child. However, one problem that resulted was gender inequality. During the Mao years, the male to female ratio was 103:107, a figure that witnessed a gradual increase over the years, eventually reaching the 2009 statistics of 100:119. Such inequality led to the difficulty of marriages for girls, causing another wave of propaganda advertising the image of families having a girl as ideal. In recent years, the policy became less strict. Many families can now afford to pay a fine to have a second child, and if two only-childs marry, they may have two children. However, many people are now abstaining from having more children because society's attitudes towards family has undergone a fundamental change and parents now want to devote more energy at work than at home. Fluent in Chinese, Hesketh narrated a personal anecdote of frequently hearing taxi drivers lamenting "too many people" (人太多)as soon as she steps into a taxi in China. She also recounted her experience of conversing with native Chinese who revealed an ignorance of the fact that other countries have no such policy! Whether be by force or by choice, having one child led to the issue of abortion, because, statistically 80% of women did not have access to contraception in 2001. Traditionally, most scholars believed that this is not a problem in the anti-Christian Chinese culture, which was greatly influenced by the Confucius idea that life begins at birth. However, recent surveys have found that such assumptions are incorrect because over half of the female population actually believes that life begins at the moment of fertilization, and that only 3.9% believes that it begins at birth. Such reality also makes the research of stem cells problematical as such attitudes will prevent women from donating embryos. Facing such social pressure, stem cell researchers are trying their best to stifle public discussions of stem cell research, because they believe that women who are willing to donate are from lower social-economic classes and would stop donating when they discover that such research, if successful, will produce advanced medicines which they cannot afford. Thus, China's scientific future, its historical policy and social attitudes are together reshaping the Chinese identity in a complex way. Chinese Arts and Performances As a part of the Symposium, the audience was also invited to view and participate in three art performances that questioned the concept of identity. Brendan Fan's project consisted of several people handing out his name cards to newly arrived guests and introducing themselves as "Brendan Fan", deliberately causing a confusion that challenged the inherent value of name cards to represent one's identity. Seaming To, a vocalist, multi-instrumentalist and composer, mixed influences from her Chinese heritage with her childhood stories to create a set of pieces reflecting upon the nature of fantasy versus reality. Along with the accompanying musicians Semay Wu and Paddy Steer, she gave an intriguing music performance. Yuen Fong Ling adapted the traditional game of "Chinese Whispers" into a drawing performance, where a group of guests were invited to each copy the sketches of the previous artist, with the first person copying a photograph of artists drawing pictures. It challenged the concept of truth in an innovative way and created a fantastic opportunity for guests to be a part of the performance itself. Wellcome's 8 Rooms, 9 Lives The Chinese Symposium took place within the wider context of Wellcome Trust's new collection 8 Rooms, 9 Lives which questions the concept of identity through the lives of 7 individuals and a pair of twins, all of which have a distinct and controversial element of identity that provoked thoughts on the subject of identity. For example, April Ashley, the first person in the UK to undergo gender reassignment struggled for 35 years to have her gender identity legally recognized. Another example is Fiona Shaw, an actress who refuted the separation between her personal and professional identities by explaining that she becomes more of herself through the process of acting another. "This exhibition takes a look back through history both at how science has attempted to determine human identity and at how we ceaselessly try to determine our own sense of self," explains James Peto, senior curator at Wellcome Collection. This collection will be available at the Wellcome Trust until 11th April 2010. As a concluding note, I'd like to draw on an anecdote told by a member of the audience from the symposium. When this lady arrived in China, she was immediately confronted with the problem that her colleagues would only translate a part of Chinese people's speeches for her so she always felt that something was untold. One day, she talked to a 6 year old child, who spoke for a long time. Immediately afterwards, she asked her friends to translate, and was given partial versions by several people, explaining that the boy was speaking about rather boring subjects. She believed this unquestioningly until a week later, someone told her, "by the way, you know that boy you were speaking to? He talked to you with the language and tense in Chinese as if he was addressing a servant." This revelation shocked her, and made her think about the reliability of any facts she accepts. I believe that this story is particularly relevant to the process of questioning identity for that no facts we know can be taken as absolute and that no viewpoints we hold can definitely remain unchanged, because knowledge and beliefs are constantly transformed through interpretations. One needs to be open to different possibilities and constantly question the nature of knowledge, as this is the only way to correctly explore our Chinese identity in a global and cosmopolitan world.

Cecily Liu

|

|