|

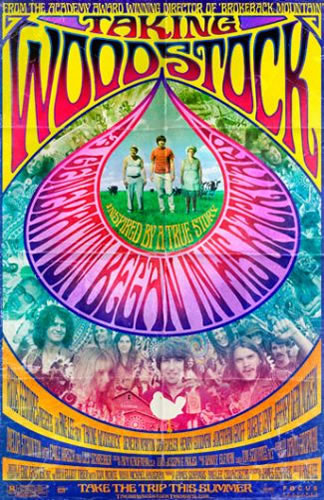

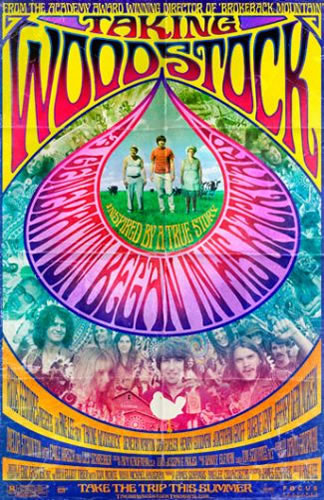

So Ang Lee’s latest box office release, Taking Woodstock is a ‘light-hearted comedy’ that chronicles the events leading up to the festival during that Summer. So Ang Lee’s latest box office release, Taking Woodstock is a ‘light-hearted comedy’ that chronicles the events leading up to the festival during that Summer.

Set in 1969, it recalls the memoirs of Eliot Tiber, the real-life inadvertent co-creator of the generation defining Woodstock music festival. Billed as ‘three days of peace and music,’ 186,000 revellers bought tickets to the event at which crowds would later swell to over half a million. The socio-political box may have been ticked off nicely in Tiber’s having found himself ‘empowered’ by the gay rights movement; but there is something distinctly superficial and non-challenging about even this.

I see Taking Woodstock has its own Facebook page. Upon closer inspection, I notice Woodstock has been ambitiously described as an experience that “changed American culture forever”. In fact, wasn’t Woodstock actually supposed to the very pinnacle, the epitome, of the hedonistic swinging sixties? The calm before The Ice Storm (1997) (so to speak) of political scandal that was to follow? Let’s get one thing straight Focus Features: American culture defined Woodstock, not the other way round.

Maybe it is the fact that with Taking Woodstock, Ang Lee appears to be simply foregoing all the elements that makes a good Ang Lee film? The Wedding Banquet (1993) was a riot of critical commentary, and it became the highest grossing film of that year, surpassing Jurassic Park even. It was a coy, comedic portrayal of an inter-racial homosexual couple living in America, bound by the constraints of that oh-so Asian concept of filial piety. It showed the modern Chinese woman as a beer-swigging, bra-defying artiste; and it even dared to portray the homosexual couple as just that, a couple. Not a rice queen and his dandy fancy man – but two reasonably successful, reasonably attractive men. Wei-Wei might have been a bit of an über-woman (I don’t see why she couldn’t have worn a bra), but the story was intriguing and probing. It played with stereotypes, crossed ethnic boundaries, and its bilingualism made it accessible to both Chinese and Western audiences – quite a feat.

Aside from the homosexual element which underlies both Taking Woodstock and The Wedding Banquet, Taking Woodstock is perhaps more obviously viewed as the pre-cursor to Lee’s markedly cynical The Ice Storm, mentioned above. Set in 1973, it is a vignette of life post- Summer of Love, the Watergate Scandal, and - lest we forget - that seminal porno-chic piece, Deep Throat (1972). There is a romance – an innocence – amongst Westerners about the “Summer of ’69” concept. I’m not entirely sure that a Chinese audience will place this film within that context. Certainly, the contrast between the free-love merry-go-round of the sixties, and the multitude of political disasters that rumbled relentlessly on in America throughout the seventies, provides an interesting theme for comparison. But that is not what Taking Woodstock, nor indeed The Ice Storm does.

So is Taking Woodstock really an “inoffensively American movie”? Can a film, in spite of its American plot, cast, setting and language really be classified as American, if its director is Taiwanese? Lee was, of course, the accomplished director of the devastatingly quaint adaption of Jane Austen’s novel Sense and Sensibility (1995). Even considering the fact that it was his first film to be produced outside of Taiwan, he managed to convey Austen’s sense of Englishness so successfully that the characters might as well have been moaning about the weather and binge drinking (and that certainly would have made reading the text at A Level more interesting). It is a problematic concept, and the very artistic nature of film-making is averse to being pigeonholed in such a way. Lee is undoubtedly an anomaly in the world of Hollywood directors. But my underlying argument here is that Lee is not just any director; he has the unique ability to capture the minutiae of life (American, Chinese, English or otherwise), in a way that has made him one of the Gods of Hollywood directorship. He has proved that with Brokeback Mountain (2005), he is able to take a subject completely removed from his own life experiences - “what do I know about gay ranch hands in Wyoming,” he is reported to have asked – and develop themes which relate to any audience; regardless of race, gender or sexuality. So is Taking Woodstock really an “inoffensively American movie”? Can a film, in spite of its American plot, cast, setting and language really be classified as American, if its director is Taiwanese? Lee was, of course, the accomplished director of the devastatingly quaint adaption of Jane Austen’s novel Sense and Sensibility (1995). Even considering the fact that it was his first film to be produced outside of Taiwan, he managed to convey Austen’s sense of Englishness so successfully that the characters might as well have been moaning about the weather and binge drinking (and that certainly would have made reading the text at A Level more interesting). It is a problematic concept, and the very artistic nature of film-making is averse to being pigeonholed in such a way. Lee is undoubtedly an anomaly in the world of Hollywood directors. But my underlying argument here is that Lee is not just any director; he has the unique ability to capture the minutiae of life (American, Chinese, English or otherwise), in a way that has made him one of the Gods of Hollywood directorship. He has proved that with Brokeback Mountain (2005), he is able to take a subject completely removed from his own life experiences - “what do I know about gay ranch hands in Wyoming,” he is reported to have asked – and develop themes which relate to any audience; regardless of race, gender or sexuality.

Yet, dare I say it; Taking Woodstock is the sort of film that could have been made by just any Hollywood director, although I will avoid launching into deeply treacherous waters with any teacherish “Ang Lee must try harder” advice of my school years. Critically, Taking Woodstock is an easy target. It lacks the probing social commentary demonstrated in his earlier films, and it isn’t nearly so bold as to introduce a classic Chinese genre such as wuxia into the mainstream (I am, of course, referring to Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon here [2000]). However, having recently returned to Chinese film with Lust, Caution (2007), Lee has proved that he is not shy to veer occasionally away from Western mainstream audiences. As such, I would like to point out that I’m not about to hop onto any premature ‘Ang Lee is a sell-out!’ band wagon just yet. But I do believe that there is something fundamentally lacking in this film. But perhaps I should try not to get my intellectually snobbish back up quite so quickly, and remember; it is Woodstock’s 40th birthday after all. |

So Ang Lee’s latest box office release, Taking Woodstock is a ‘light-hearted comedy’ that chronicles the events leading up to the festival during that Summer.

So Ang Lee’s latest box office release, Taking Woodstock is a ‘light-hearted comedy’ that chronicles the events leading up to the festival during that Summer. So is Taking Woodstock really an “inoffensively American movie”? Can a film, in spite of its American plot, cast, setting and language really be classified as American, if its director is Taiwanese? Lee was, of course, the accomplished director of the devastatingly quaint adaption of Jane Austen’s novel Sense and Sensibility (1995). Even considering the fact that it was his first film to be produced outside of Taiwan, he managed to convey Austen’s sense of Englishness so successfully that the characters might as well have been moaning about the weather and binge drinking (and that certainly would have made reading the text at A Level more interesting). It is a problematic concept, and the very artistic nature of film-making is averse to being pigeonholed in such a way. Lee is undoubtedly an anomaly in the world of Hollywood directors. But my underlying argument here is that Lee is not just any director; he has the unique ability to capture the minutiae of life (American, Chinese, English or otherwise), in a way that has made him one of the Gods of Hollywood directorship. He has proved that with Brokeback Mountain (2005), he is able to take a subject completely removed from his own life experiences - “what do I know about gay ranch hands in Wyoming,” he is reported to have asked – and develop themes which relate to any audience; regardless of race, gender or sexuality.

So is Taking Woodstock really an “inoffensively American movie”? Can a film, in spite of its American plot, cast, setting and language really be classified as American, if its director is Taiwanese? Lee was, of course, the accomplished director of the devastatingly quaint adaption of Jane Austen’s novel Sense and Sensibility (1995). Even considering the fact that it was his first film to be produced outside of Taiwan, he managed to convey Austen’s sense of Englishness so successfully that the characters might as well have been moaning about the weather and binge drinking (and that certainly would have made reading the text at A Level more interesting). It is a problematic concept, and the very artistic nature of film-making is averse to being pigeonholed in such a way. Lee is undoubtedly an anomaly in the world of Hollywood directors. But my underlying argument here is that Lee is not just any director; he has the unique ability to capture the minutiae of life (American, Chinese, English or otherwise), in a way that has made him one of the Gods of Hollywood directorship. He has proved that with Brokeback Mountain (2005), he is able to take a subject completely removed from his own life experiences - “what do I know about gay ranch hands in Wyoming,” he is reported to have asked – and develop themes which relate to any audience; regardless of race, gender or sexuality.